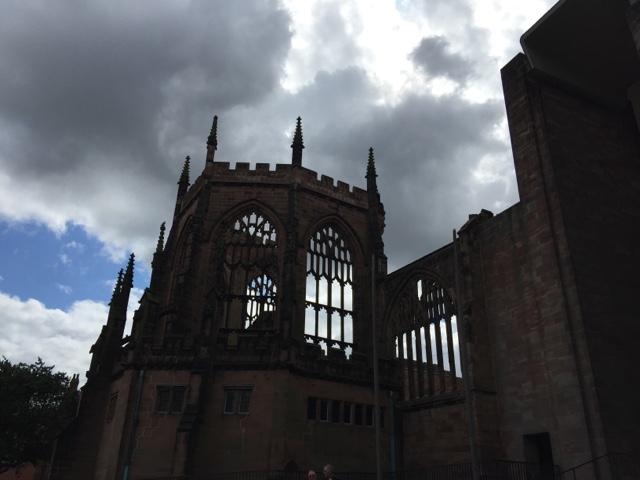

Seven days ago I stood in the midst of what is perhaps Britain's greatest and also most challenging war memorial, the bombed out ruins of Coventry Cathedral. It has taken a full week for me to process the experience of that place and all the modern nightmare and eternal vision it represents. Now I am ready to write and to share that experience, to share my own experience of Britain's greatest testament to the hope for peace and for reconciliation amongst all peoples and nations. And I share it on a day when such a testament is called for, necessary even -- August 6, 2015, the 70th anniversary of the dropping of the atomic bomb on Hiroshima, Japan.

A Story We Can't Ignore

On the night of November 14, 1940, German Luftwaffe unloaded a massive aerial bombardment on the city of Coventry in the northwest of England. Six hundred civilians died in the blitz which decimated much of the city and brought its medieval cathedral to rubbled ruins.

It was there, amidst the death and destruction, that a fateful decision was made which would transform the life of the Cathedral and its calling in the world. Resisting the desire for vengeance, the Cathedral's leader, Provost Dick Howard, directed that the words "Father Forgive" be inscribed in the still-standing walls of the burned-out Cathedral sanctuary. Then, just weeks after the bombing, Howard stood inside the ruins and broadcast a Christmas Day message on BBC in which he said:

"What we need to tell the world is this: that with Christ born again in our hearts today, we are trying, hard as it may be, to banish all thoughts of revenge . . . We are going to try to make a kinder, simpler, a more Christ-like sort of world in the days beyond this strife."

Thus began Coventry Cathedral's new ministry as a symbol of forgiveness and hope. That hope is embodied, Phoenix-like, in the very architecture of the Cathedral, as a stunningly modern and lucid new church rises up above the preserved walls of the old. The two buildings, side by side make a stunning visual image -- one a memorial to the lives lost to the brutal cost of modern and mechanized weaponry, and the other a sign of the human community's ability to heal from the wounds of war.

Howard's words and the Cathedral's mission are at once inspiring and yet also disturbingly difficult. But regardless of how unsettling Coventry might make us feel, in the end what is written in the Cathedral literature is deeply true: It is a story we can't ignore.

Service of Reconciliation

While at Coventry Irie and I attended the noon Service of Reconciliation in the new Cathedral nave. The service is short and led by deacon who tells the story of the Coventry and then leads the congregation in a simple, yet deeply profound Litany of Reconciliation.

The Litany begins with a confession from St Paul's Epistle to the Romans, "All have sinned and fallen short of the glory of God." Then there is a series of seven repetitions where the deacon names the deadly sins of hatred, covetousness, greed, envy, indifference, lust, and pride, each followed antiphonally by the congregation praying in unison, "Father, forgive." The service ends with the deacon this time quoting Paul's Epistle to the Church at Ephesus: "Be kind to one another, tender-hearted, forgiving one another, as God in Christ forgave you." The deacon then invites those present to take the litany and the whole Coventry story back with them to their home congregations.

As I sit here with the litany before me I notice what the liturgy is attempting to teach us in its form. The service both begins and ends with a reminder that we are all sinners and in need of forgiveness. It is the Cathedral's way of teaching us that all reconciliation must begin and end with our own humility and confession. This is the way toward reconciliation that Coventry seeks to teach the world; and it is the way toward reconciliation it invites us to go and teach also.

A Place of Images

Yet even more than liturgical words, Coventry is a place of liturgical images. And I leave you with two images from my visit.

The first comes from among the many striking pieces of art to be found in and around the Cathedral. There is the bold bronze of St Michael standing victorious over Satan -- a sign of the ultimate triumph of good over evil, right outside the entry way of the new Cathedral. Then there is the Charred Cross, made from two medieval wood beams found in the shape of the cross after the Cathedral bombing. And of course, the whole Cathedral itself is an astonishing work of beauty and art.

But the image I want to share is the sculpture by Josefina de Vasconcellos titled "Reconciliation". It is the image of a man returning from war to meet his wife at home. Together, they bend or fall to their knees in loving embrace. It is a beautiful image of both the heartache of separation and loss and also the joy of reconciliation. The reason I choose to share this image on this August 6 day is because as one of these sculptures stands near the back of the narthex in the new Cathedral another twin copy of the sculpture has been placed on behalf of the people of Coventry in the Peace Garden in Hiroshima. Faceless, yet locked in the embrace of universal love, the couple of "Reconciliation" remind us of the inherent humanity of all those caught up in the tragedy which was World War II and all other wars before and after.

The other image I want to share I myself captured. I was standing in the middle of the hollow ruins of the medieval Cathedral when I turned to look eastward and was startled to see a young child, perhaps two or three years old, sitting near the sanctuary altar, calm and still on the stone floor just beneath the words "Father Forgive". The mother of the child was just getting up to come and scoop the little girl up as I rushed to capture the moment with my camera. I made it just in time and this image is for me now my favorite image of all the images from this entire trip to England.

I have had the week to reflect upon the meaning of this child, in all her beauty and innocence, sitting inside the canopy of a memorial to the great human cost of war, the words from our Lord and Savior somehow gathering the two together in a kind of harmony of space and time. What is the meaning of this moment -- of this image, of this child before this altar? I cannot say what the meaning is for anyone else but for me. That is the beauty of an image -- it speaks with more nuance and meaning than words.

But as I do speak for myself I speak of two more images which are evoked -- one from the Old Testament and the other from the New. The Old Testament image is from the Prophet Isaiah, who in a vision for a time yet to come spoke of the hope-filled day when wolf will live with lamb, leopard will lie down with goat, and calf with lion; and a little child will lead them all. And the New Testament image comes from that scene where Jesus sits a little child between his disciples and tells them that if they wish to enter the kingdom they must change and become like the child.

And I wonder if that might be it for me -- the meaning of this child before this altar. That for me this child might have been sent there to as a sign to lead us into some more hope-filled time and kingdom yet unrealized, but only if we are willing first to change first. Only if we are willing to deeply confess our own sin personal and corporate and the cynicism we have about this world, its violence and God's ability to change us. Only if we are willing to have our hearts changed and believe once again in the hope and prospect of forgiveness and reconciliation within ourselves, our families, our churches, our communities, and our world. In other words, only if we are willing to become like this child, and sit down silently at the altar, and wonder again at the meaning of the words on the wall:

"Father Forgive."

No comments:

Post a Comment